There has been quite a lot in the press recently about how the freight industry is trying to meet its carbon targets. In July the global shipping industry agreed to achieve net-zero by around 2050, updating the previous 2018 agreement to reduce carbon emissions by half by the same date. There are interim targets but they are vague – the industry should strive to cut emissions by 30% by 2030 and 80% by 2040.

The global shipping industry is critical to world trade carrying 90% of commercial goods. But it is also responsible for a significant amount of carbon emissions. Ships produce around 3% of global CO2 because of the carbon heavy fuels used to power ships. This is around the same amount as Germany.

The proposed reduction in emissions might be difficult to achieve. Not all countries were in agreement with the targets and the ownership of vessels means enforcing them may be difficult. Maritime transport is hard to regulate as ships are often owned in one country but registered with another. Small states like the Marshall Islands, Liberia and Panama have huge numbers of ships sailing under their national flags but they have no real responsibility for these vessels.

Interestingly, one of the possible ways in which the carbon emissions might be reduced is by using sails. This started on a small scale with the reintroduction of old fashioned sailing barges by enthusiasts concerned about the use of heavy fuels in the shipping industry. These boats are small and their use tends to be restricted to shorter or inland routes, for example along the Hudson River in New York State.

But now attention has turned to the larger cargo vessels that can be enormous – the largest can move 20,500 containers, and have a total weight of 210,000 tonnes. The idea is to fit these with giant rigid sails in order to cut fuel consumption and therefore shipping’s carbon footprint. The hope is that this could cut carbon emissions by 30%, but there are issues. The sails may not be suitable for all vessels as they could inhibit the loading and unloading of cargo. However, it is one of a series of measures, including looking at alternative fuels, that could help the industry to meet the zero emissions target.

Freight Margin Rate

This is all very interesting, but does it have any impact on margin requirements for freight contracts?

There are a range of derivatives available for trading. For example the Baltic Exchange, that sets the benchmark for freight around the world, partners with CME, EEX, ICE and SGX in providing futures and options.

The prices for freight have been highly volatile over the past year. The Baltic Freight Index was at a low of 525 on 17th of February. By 10th of May it had hit a high of 1650, with the current rate hovering around 1200. This has been caused by a number of factors including the ongoing volatility in fuel prices resulting from the Russian invasion of Ukraine, alongside bad weather conditions coming from a combination of climate change and El Niño.

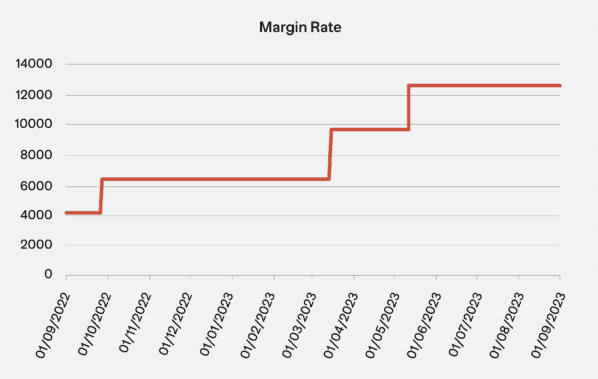

The same volatility is reflected in the margin requirements for freight contracts. The following chart shows the margin rate for front month Capesize Timecharter (Baltic) Freight futures at ICE over the past year:

It can be seen that as the price increased so did the margin requirements. However, although prices have fallen from their highs, the margin has remained high and now represents a much higher percentage of the contract value. This clearly indicates the different influences on the level of margin requirements. Price is important but so too is volatility. The level is usually set using Filtered Historical VaR, which means that historical price moves will be a prime input into the calculation, but so too will be the current levels of volatility.

As it is unlikely that volatility will drop given the continuing geopolitical uncertainty and extreme weather events, it is likely that margin requirements will remain high for the foreseeable future.