With the lower levels of volatility now prevalent in the commodity markets, firms are looking at alternatives that may give them the potential for profits that they seek. With US products showing higher levels of volatility we looked at the differences between this and the European markets.

But some firms may not be willing or able to take on the changes in regulation a move to a different market implies. And this is without taking into account the differences in the Initial Margin algorithms that would need to be supported.

An alternative is to look to change the products that are traded. A move from financial to physical could be enough to provide the additional volatility. But this comes with additional complexity. The most obvious is the need to participate in the delivery process. But there are also differences in the margin requirements – in particular the need to pay Delivery Margin.

Understanding Delivery Margin

Most traders are aware of Initial and Variation Margin, but Delivery Margin is less well understood, especially as it only impacts contracts that go to delivery. Whilst many contracts are cash settled, and therefore not subject to Delivery Margin, even for those that are very few firms take their positions to delivery, instead choosing to roll their trades ahead of expiry.

The problem with Delivery Margin is that there is no standard way of calculating it. There may be different Initial Margin algorithms, but they are all predicting potential future exposures over a short time horizon for contracts with a daily settlement price. Delivery Margin needs to cover potential losses that are dependent on the delivery mechanism.

The way that collateral is applied can also differ depending on the product and the CCP. For some the collateral pool applied to Initial Margin is used, whereas others use separate accounts for delivery. For these, it is often the case that the Delivery Margin must be paid in cash.

Examples of delivery margin include:

- Initial Margin is calculated on short positions only to cover the risk of the seller not making the delivery and the CCP being obliged to use the spot market to purchase the commodity, by which time the price could have increased.

- Contingent Variation Margin is calculated on the contract based on the difference between the final settlement price and current market price until delivery is completed.

- Both buyers and sellers are required to post cash equal to the final settlement price of the contract into a separate delivery account.

- Additional margin is calculated to cover potential charges based on delivery failures, for example “system buyout price”. This can be an initial estimate which is then adjusted throughout the month as the daily charges are known.

These different styles of Delivery Margin are sometimes combined making the calculation even more complex. As an example, for TTF Dutch Gas futures at ICE the following components are combined:

- Buyer’s and Seller’s Security

- Buyer’s Default Top Up and Seller’s Default Price to cover potential charges for delivery failure

- Contingent Variation Margin

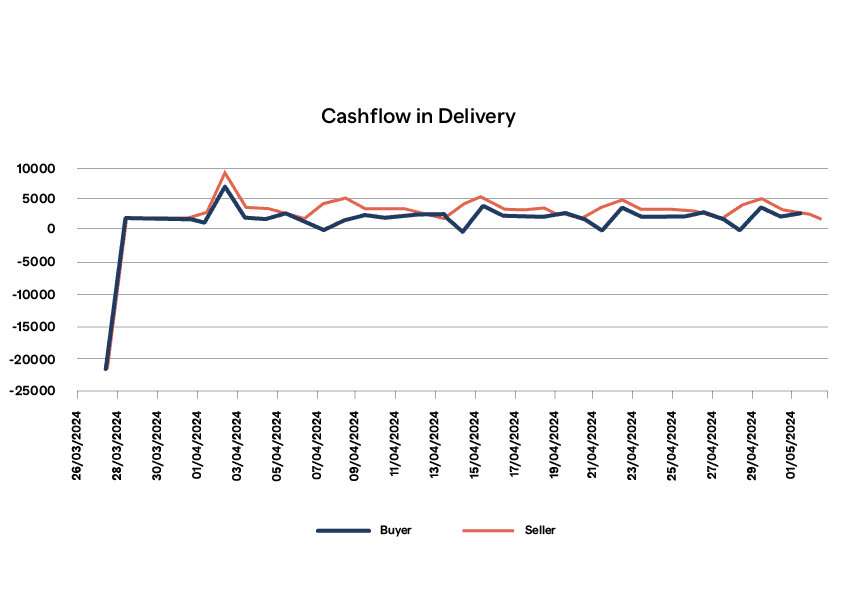

When considered together these requirements can result in varying impacts on cash flow over the delivery month:

The main impact is the need to pay Buyer’s and Seller’s security on expiry, but the fluctuation in CVM means that cash flow can be impacted throughout the delivery period.

Conclusion

It can be seen from these examples how complex and varied the calculation of Delivery Margin can be. And it can also be a significant part of any margin call.

If you are going to swap trading financial derivatives for physical then you need to make sure that you don’t just consider the issues that going to delivery will bring. You also need to consider the difference in the way that margin is calculated and in particular ensure that you are able to understand Delivery Margin.